Beyond Access Part 5: What Strong HQIM Integration Looks Like for Programs

A Five-Part Series on HQIM Readiness in Teacher Preparation

When Preparation Fails the Candidate

She arrives at student teaching ready to plan & facilitate her first unit. The district has fully adopted high quality instructional materials, and her mentor sets a thick binder on the table. She flips through the lessons, realizing this is the first time she has ever been asked to use them. In coursework, she only saw fragments. In methods, she built units from scratch. Her clinical supervisor still only expects generic lesson plans based on topics or subject areas of interest. She really likes her mentor teacher, and she’s heard that her mentor is a really great teacher. She doesn’t want to let her down, but more importantly she wants to meet expectations and not let her P-12 students down.

She wonders: if my program never prepared me to use these materials, how am I supposed to be ready now?

Why Program Design Matters

High quality instructional materials will not get implemented by candidates or teacher educators through good intentions. They get implemented through strong program design. For candidates to develop the skills and habits needed to use HQIM with precision, programs must build and sustain systems with teacher educators that create consistent development across every experience: coursework, clinical practice, data routines, and feedback expectations.

This requires more than a handoff from one teacher educator to another, or a collection of isolated assignments. It demands structural alignment across the program. Too often, compliance approaches are mistaken for readiness. A curriculum map is created, a planning task is inserted into one course, or a resource room is stocked with instructional materials. These efforts check a box but do not prepare candidates. Exposure without deliberate design leads to improvisation, not readiness.

Research bears this out. National studies have found that candidates often graduate from preparation programs without meaningful experience using district curricula, and as a result many enter classrooms improvising their approach to grade level instruction. The Opportunity Myth showed how this gap contributes directly to students being denied access to rigorous content. In contrast, when preparation programs embed curriculum use systematically, candidate readiness improves. In Tennessee’s HQIM network, for example, the share of teacher candidates making decisions that supported rigorous instruction rose from 45 percent to 77 percent after program-level modules were introduced.

Programs that make HQIM central to their design send a different message. Southeastern Louisiana University requires candidates to engage in structured internalization and rehearsal cycles using district-adopted curricula, with supervisors and mentors trained to provide aligned feedback. Dallas College redesigned its coursework so that candidates analyze and teach real lessons from Eureka Math and Amplify Reading, ensuring that practice reflects what they will encounter in schools. These examples show that HQIM readiness does not emerge from access alone - it requires program design.

Programs that make HQIM central to their design ensure that candidates rehearse with the same materials they will be expected to teach, receive feedback from faculty and clinical supervisors who share consistent expectations, and experience developmental growth that is measured and reinforced at every stage.

Program Structures That Anchor HQIM Readiness

Strong programs make high-quality instructional material use a design choice, not an add on. The goal is simple and ambitious. Every candidate experiences deliberate, repeated practice with the high-quality instructional materials they will need to identify, and/or use to teach. Every teacher educator models, rehearses, and coaches the same expectations. Every decision about coursework, clinical, and assessment points candidates toward day one readiness. The structures below turn that aim into a plan.

1. Understanding District Context

We covered this in depth in Part 2 of Beyond Access. The point here is direct. Programs cannot prepare candidates for curriculum readiness without knowing what their district partners actually use. That means more than assuming or referencing a resource room. It requires going to see for yourself, clarifying expectations, and designing preparation around that picture so candidates rehearse and enact what they will one day be responsible for.

Key steps

- Identify which curricula are in use by grade and subject.

- Clarify district expectations for how those materials must be implemented.

- Surface common challenges, misconceptions, and supports that teachers receive.

- Define what strong implementation looks like in classrooms.

Program routines

- Convene a partner group each term to review the curriculum landscape.

- Conduct site visits and co-observations to see materials in practice.

- Engage faculty, clinical supervisors, and mentors in reviewing candidate tasks for alignment.

Artifacts and decisions

- A curriculum landscape brief that shows which materials are adopted and where candidates are placed.

- Short curriculum profiles outlining lesson structures, routines, and non negotiables.

- Placement and mentor selections that guarantee authentic curriculum practice.

2. Shared Vision for HQIM Ready Candidates and Teacher Educators

Candidates and teacher educators cannot work from different playbooks. Programs must define what success looks like for both, make it explicit, and reinforce it everywhere. Without a shared vision, candidates receive mixed messages and faculty or supervisors default to personal preference. With a shared vision, everyone speaks the same language, uses the same criteria, and holds to the same expectations.

Expectations for candidates

- Identify and select materials that are standards aligned and rigorous.

- Internalize lessons with clarity of goals, anticipated student thinking, and planned moves.

- Adapt for access while preserving rigor and lesson intent.

- Facilitate instruction responsively with purposeful pacing, questioning, and checks for understanding.

Expectations for teacher educators

- Model and label curriculum moves in their own teaching.

- Provide rehearsals that mirror real classroom use.

- Deliver specific, timely, and aligned feedback tied to shared criteria & ‘look fors’.

- Calibrate expectations through co-observation, video review, and use of common tools.

Embedding the vision

- Syllabi, course modules, and rehearsal protocols carry the same expectations

- Observation and coaching tools reference the same look fors.

- Candidate assessments and gateways check for proficiency of the same criteria

Communication plan

- Launch the vision at the program starting with candidates, faculty, supervisors, and mentors.

- Revisit and reinforce it in each course and field seminar.

- Provide a short reference tool naming the four candidate skills and the teacher educator responsibilities.

3. Beyond Access: Prioritizing What Matters Most

Access is necessary, but it is not sufficient. Too often programs treat curriculum access as the finish line: a login, a sample lesson, or a single planning task. Exposure without depth produces shallow results. Candidates may know a material exists, but they leave without the fluency to internalize, adapt, and facilitate it with students.

Strong programs move beyond access by making deliberate choices about which curricula to emphasize and how to build candidate fluency. The goal is not to cover everything. The goal is to cover the right things, deeply and well.

Prioritization rules

- Select the few curricula that account for the largest share of placements and likely hiring.

- Begin with early literacy and mathematics, where expectations for structured instruction are most defined.

- Expand strategically once the foundation is stable, rather than spreading thin across too many materials.

Program routines

- Provide candidates with repeated practice using these materials across coursework and clinical experiences.

- Ensure every teacher educator models, labels, and reinforces the same criteria for strong curriculum use.

- Calibrate feedback so that regardless of who is coaching, candidates hear the same message about what quality looks like.

Markers of quality

- Candidates engage with priority curricula multiple times per term in cycles of analysis, rehearsal, and facilitation.

- Assignments require authentic lessons, not excerpts or substitutes.

- Faculty and mentors use shared study guides and feedback language tied to the chosen curricula.

- Evidence shows candidates can use materials with integrity and purpose, not just that they had access to them.

Being strategic about emphasis does not limit candidate preparation. It increases impact. When candidates can internalize, adapt, and facilitate high quality instructional materials with precision, they are ready for day one in any classroom, whether the district provides those same curricula or none at all. They leave with both the habits and the bar for excellence.

4. Coursework and Clinical Integration

Curriculum use cannot be siloed in one course or left to chance in clinical placements. It must be the spine of the program. Integration means threading high quality instructional materials across coursework and fieldwork in ways that are intentional, aligned, and sequenced.

Mapping the sequence

- Place the four candidate skills - identify, internalize, adapt, and facilitate - across the program in a clear progression.

- Link assignments and performance tasks (signature tasks, etc.) in coursework to authentic lessons from priority curricula.

- Connect clinical experiences so candidates have daily opportunities to practice those same routines with students.

- Use artifacts and gateways to confirm growth at each stage.

Design rules for coursework

- Assignments require real lessons, not excerpts or contrived activities.

- Each major task includes rehearsal, feedback, and revision before candidates attempt full enactment.

- Faculty model and label curriculum moves in class, then coach candidates to do the same.

Design rules for clinical

- Select placements where priority curricula are consistently in use.

- Ensure mentors and supervisors apply the same look fors and feedback language as faculty (and vice versa).

- Build co observation into each term so teacher educators calibrate expectations together.

Cadence of practice with aligned feedback

- Early term: analysis and approximations/representations (rehearsals).

- Rest of term: rehearsal, targeted adaptation, and full lesson enactment with reflection on P-12 student impact (e.g. evidence of student learning).

Integration is not about exposure. It is about fluency. When coursework and clinical are mapped together, candidates experience a coherent path where each stage of preparation reinforces the last. Faculty, supervisors, and mentors all point to the same expectations, creating the consistency needed for candidates to be ready on day one.

5. Data That Drives Improvement

You cannot improve what you do not measure. Programs must build data routines that track both candidate growth and teacher educator practice with curriculum. Without evidence, leaders rely on impressions. With evidence, they can spot breakdowns, adjust supports, and strengthen the program.

What to measure

- Candidate progress on internalization, adaptation, and facilitation across courses and terms.

- Teacher educators practices include modeling, rehearsal, and feedback.

- Placement quality and whether candidates have daily opportunities to practice with priority curricula.

- Effectiveness of coursework tasks in building fluency.

- Student learning evidence from candidate lessons where available.

Tools and artifacts

- A tracker that captures candidate skill growth with notes on evidence.

- A calibration log showing agreement across faculty, clinical supervisors, and mentors.

- Placement profiles documenting curriculum use and opportunities to practice.

- End of course and end of placement surveys that surface candidate experiences with curriculum.

Routines and cadence

- Monthly meeting to review snapshots and plan small adjustments.

- Mid term reviews to check gateway pass rates and target support.

- End of term reviews with faculty, clinical supervisors, and P-12 district partners to set priorities for the next cycle.

How to use the data

- Revise coursework and clinical supervision practices.

- Run calibration sessions when feedback quality varies.

- Adjust placement lists if candidates lack sufficient curriculum practice.

- Scale assignments or tasks that consistently drive strong growth.

Data is not about compliance. It is about quality. The anchor questions apply every term: Are candidates day one ready? How do you know?

Putting it All Together

The structures described above give programs a clear path for designing HQIM readiness that is consistent, intentional, and measurable. Each structure - understanding district context, defining a shared vision, moving beyond access, integrating coursework and clinical, and using data for improvement - reinforces the others. Together they form the system that turns candidates’ curriculum exposure into curriculum readiness.

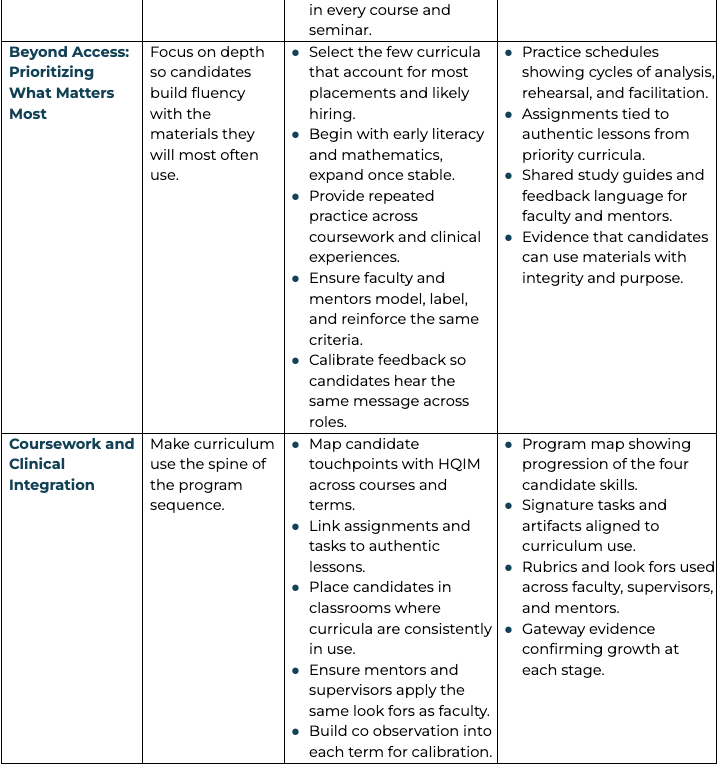

A detailed table in the appendix summarizes these structures into specific actions, program routines, and artifacts. It is designed as a practical tool for program leaders to adapt and apply within their own context.

Series Conclusion: Beyond Access

Across this series we have followed a simple but urgent truth: access alone does not prepare teachers. In Part 1, we saw how too many candidates first encounter the curriculum as a sealed box, unpracticed and unfamiliar. In Part 2, we examined the need to align preparation with the materials districts actually use, rather than assuming exposure is enough. Part 3 showed what readiness means for candidates themselves - developing the skills to identify, internalize, adapt, and facilitate curriculum with integrity. Part 4 shifted the lens to teacher educators, whose modeling, rehearsal design, and feedback practices determine whether candidates experience coherence or confusion. And in Part 5, we have highlighted that program design is the anchor that holds it all together.

The message is clear: strong preparation does not happen by chance. It is the result of deliberate program structures, aligned expectations, intentional partnerships, and teacher educator development that centers high quality instructional materials at every stage. When programs commit to this work, candidates stop improvising and start teaching with clarity and confidence. District investments in HQIM pay off, novice teachers enter classrooms day one ready, and P-12 students, especially those furthest from proficiency, gain consistent access to the grade level instruction they deserve.

The challenge now is for preparation programs, states, and funders to move beyond pilot efforts or surface compliance and make HQIM readiness non-negotiable. The research is compelling, the steps are clear, and the examples are growing. What remains is the will to act. Let us ensure that no candidate leaves a program still opening the box for the first time.

Let’s make teacher preparation better together.

Appendix

What Strong HQIM Integration Looks Like for Programs

Stay Connected

If you're interested in learning more, exploring collaboration or technical assistance, or just want to catch up, we’d love to connect:

About EdPrep Partners

Elevating Teacher Preparation. Accelerating Change.

EdPrep Partners is a national technical assistance center and non-profit. EdPrep Partners delivers a coordinated, high-impact, hands-on technical assistance model that connects diagnostics with the support to make the changes. Our approach moves beyond surface-level recommendations, embedding research-backed, scalable, and sustainable practices that most dramatically improve the quality of educator preparation—while equipping educator preparation programs, districts, state agencies, and funders with the tools and insights needed to drive systemic, lasting change.