The Coaching Gap: Moving From Chance to Design

The Coaching Gap: Moving From

Chance to Design

Implementing Coaching Systems Every Candidate Can Count On

Why Coaching Forecasts Readiness

Clinical and internship teaching are often cited as the most impactful portions of teacher

preparation for two reasons: they allow candidates to enact instructional practices with P-12

students, and they provide iterative coaching from faculty, clinical supervisors, mentors, and peers. Yet across both coursework and clinical experiences, feedback remains inconsistent and often falls short. A recent study analyzing more than 11,000 supervisor evaluations and candidate reflections found that fewer than half of evaluations included a clear area for improvement or an actionable next step. Supervisors most often flagged classroom management as the area for growth, while candidates themselves highlighted lesson planning.

The quality and focus of feedback matters, and the gaps are visible in how our field is currently leveraging coaching across preparation. Meta analyses reinforce what we already know: coaching and mentoring improve candidates’ instructional skills, but not all feedback is equal. The most powerful driver of growth is when teacher educators-whether faculty in coursework or supervisors and mentors in clinical settings-model practices, make their thinking visible, and then give candidates the chance to rehearse those methods, instructional and content pedagogies, or strategies with criteria driven feedback. In programs that do this, preservice teachers show much clearer improvement in their teaching and in their ability to make lessons clear for students. Feedback alone is not enough. Feedback plus modeling and rehearsal is what moves practice.

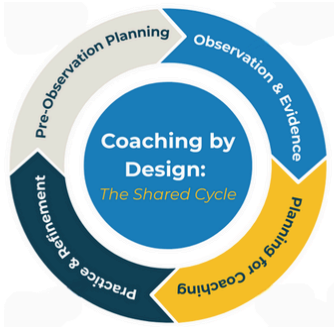

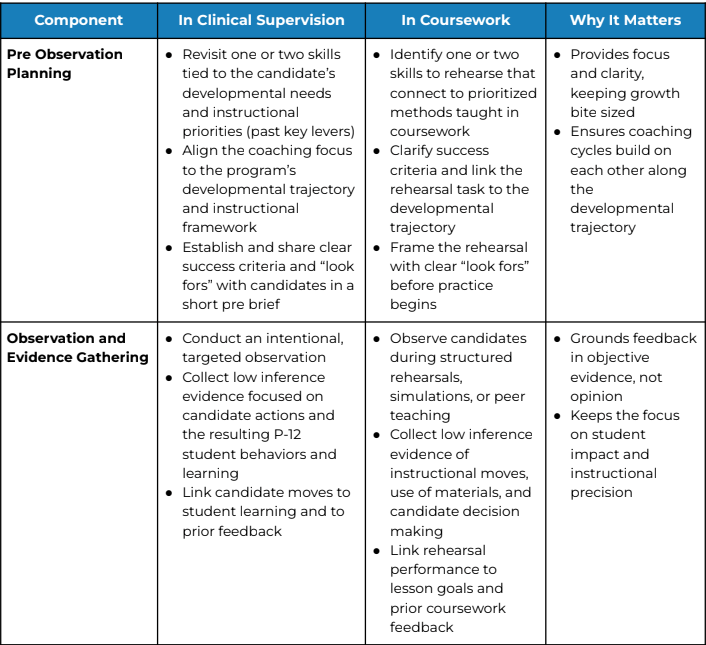

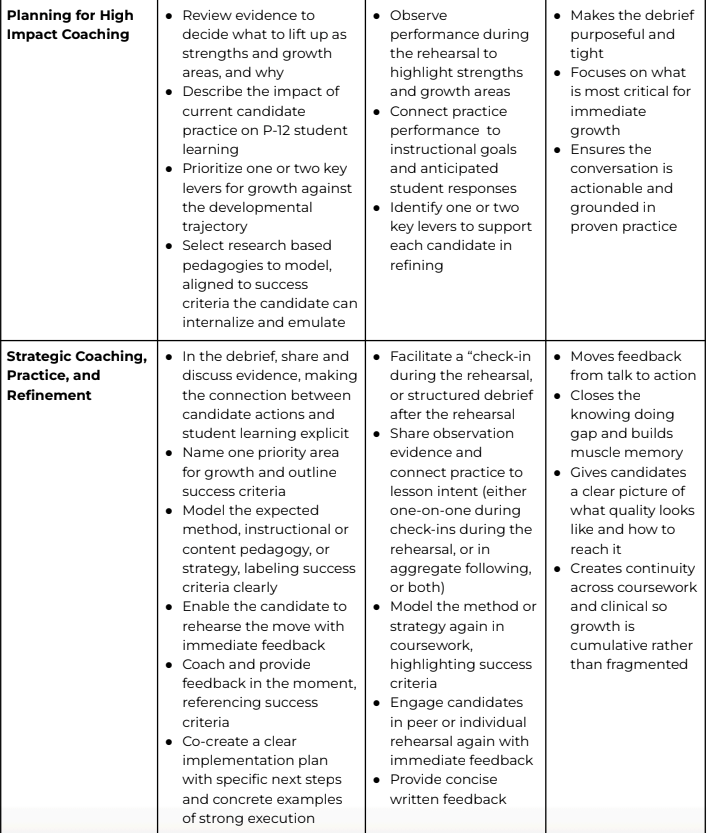

We have a system design problem, and it has become painfully clear: too often, feedback depends on an individual faculty member, supervisor, or mentor and their own experience and skill in coaching rather than on a consistent structure every candidate can count on. What is missing is a common coaching cycle: beginning with pre observation planning aligned to candidate developmental needs, narrowing to one or two refinement areas during observation, and following with evidence based debriefs that link teacher moves to student learning. High quality coaching closes by modeling the expected practice with clear criteria, giving candidates space to rehearse it, providing feedback during the rehearsal, and setting clear action steps with additional follow up. Without this structure, feedback risks being occasional advice or scattered tips rather than a deliberate system for growth.

This is the kind of challenge the field can solve together. By building on a shared approach,

programs can move from good intentions to a reliable system that ensures every candidate,

across coursework and clinical experiences, receives the coaching they need, and deserve, to be truly prepared for P-12 students.

Barriers That Prevent Quality Feedback

The inconsistent quality and timeliness of feedback to candidates is not simply a matter of

individual effort. It reflects predictable barriers in program structures and processes that most preparation programs face when coaching is not designed with intentionality.

- Coaching usually depends on the individual teacher educator. Too often, the quality of feedback rests on the interests and expertise of a faculty member, clinical supervisor, or mentor, shaped by their own experience and level of skill in coaching. Without a shared structure, candidates end up with very different developmental opportunities depending on who they are assigned.

- We wait until clinical supervision for quality, criteria driven, instructional framework based feedback. Programs often treat coursework as the place for feedback on theory, leaving the more structured, criteria based coaching tied to the instructional framework for clinical experiences. This delay means candidates miss opportunities to build their understanding of quality instruction as defined by their campus and district, to develop habits earlier and more consistently, and it reinforces the idea that coaching is an event in supervision rather than a throughline across preparation.

- Time and scheduling work against consistency. Candidates are often grouped or assigned without a clear purpose for maximizing observation and coaching, defaulting instead to logistical convenience. Clinical supervisors then juggle multiple campuses and candidates, while faculty balance coursework and other responsibilities. Without program level norms that protect and prioritize time for coaching, feedback becomes irregular or rushed. If a program intentionally partners on placements and reduces the number of campuses it serves, supervisors can spend more time observing, debriefing, and strengthening the quality of onsite supports.

- Feedback is delayed or diluted. Candidates sometimes wait days for written notes or receive general comments instead of specific, actionable guidance they can use in their very next lesson. Delayed or vague feedback loses its power to shape immediate growth and leaves candidates uncertain about what to do next.

- Coaching debriefs lack success criteria and rehearsals. Too often, post observation conversations stop at pointing out what was seen or offering general advice. Without clear criteria for what “good” looks like and without structured opportunities to rehearse the move, candidates leave with feedback they cannot immediately translate into action.

- Roles are not calibrated. Faculty, supervisors, and mentors often work from different playbooks and hold different understandings of the standard, emphasizing varied priorities or using inconsistent language. Candidates then hear mixed messages about what matters most, and their development depends more on who is coaching them than on a shared vision of quality teaching.

- Limited ongoing development for teacher educators. Faculty, supervisors, and mentors are often expected to coach without consistent training, practice, or feedback on their own coaching. Opportunities for ongoing development, including train the trainer models and observation of teacher educators themselves, are rare. Without this support, even well intentioned teacher educators struggle to provide the high quality feedback candidates need, and deserve.

These barriers are real, but they are not permanent. Each can be addressed by treating coaching as a system that ensures every candidate, in both coursework and clinical experiences, participates in the same cycle of focused observation, timely feedback, modeling, and rehearsal.

The opportunity is to move from coaching by chance to coaching by design.

Designing a Shared Coaching Cycle

The challenge in coaching within teacher preparation programs is not a lack of effort. It is the absence of a consistent system across programs that ensures every candidate receives the same quality of coaching. Coaching should be the backbone of preparation, not something only some teacher educators do (well).

In strong programs, feedback follows a predictable rhythm across both coursework and clinical experiences. Faculty, supervisors, and mentors all use the same cycle so candidates experience coaching as a system rather than a matter of chance. The structure below reflects what research and high performing programs show works in practice.

Components of an Effective Shared Coaching Cycle

The payoff: Candidates know exactly what to do next and why it matters for P-12 students.

Faculty, clinical supervisors, and mentors reinforce the same expectations in coursework and in classrooms. Programs establish a culture where coaching is the norm rather than the exception. And students benefit because their teachers enter classrooms ready to act with skill, confidence, and effectiveness. In a word, candidates are ready.

Teacher Educator Development Matters

Teacher educator development matters. For candidates to experience coaching as a reliable and impactful system, teacher educators must also be developed. Faculty, clinical supervisors, and mentors cannot be expected to deliver consistent, high quality feedback without structured preparation of their own. Strong programs build this capacity by:

- Onboarding every teacher educator into the coaching cycle practices so that faculty, clinical supervisors, and mentors share a common language and set of practices.

- Providing ongoing training that mirrors what candidates experience: modeling, rehearsal, feedback, and refinement.

- Calibrating regularly by reviewing the same candidate teaching clips in specific instructional domains or indicators, and the corresponding artifacts, and together aligning on what was observed and the expectations of quality.

- Providing feedback on coaching practice itself, observing and supporting teacher educators (including faculty and mentors, not just clinical supervisors) so they continually strengthen their ability to model, coach, and develop candidates in effective instruction.

When teacher educators are consistently trained and supported, candidates do not depend on the chance of being paired with someone who can provide quality, criteria driven feedback. Instead, every candidate benefits from a shared structure reinforced across settings, making their preparation intentional and dependable.

Measures That Show the Coaching is Working (or Isn’t)

A coaching cycle only matters if it is implemented consistently. The way to know is not through more paperwork, but by tracking a small set of measures that reveal whether coaching is happening as intended and whether it is improving candidate learning.

Strong programs focus on three types of measures:

Teacher educator quality of coaching

- Do faculty, supervisors, and mentors calibrate regularly on what “good” looks like using shared clips, artifacts, and success criteria?

- Are teacher educators modeling practices, labeling criteria clearly, and giving candidates structured rehearsal opportunities in both coursework and clinical experience debriefs?

- Are faculty, clinical supervisors, and faculty using the shared cycle and language with candidates consistently across programmatic experiences?

Implementation checks

- How many teacher educators are consistently implementing the coaching cycle, and with what frequency?

- How many candidates are receiving a full cycle in both coursework rehearsals and clinical observations? How often does this occur?

- What percentage of coaching conversations include a rehearsal with feedback, rather than discussion alone?

- How often is oral feedback provided immediately and written feedback delivered within 48 hours?

Impact and growth signals

- Are candidates improving on the prioritized skills identified in the program’s developmental trajectory? How many are on track, and how many are off track?

- Do observation records demonstrate that coaching is leading to visible shifts in candidates’ instructional practice?

- Do candidates report that feedback is timely, specific, actionable, and useful in shaping their next lesson and overall development?

These measures are simple enough to capture through coaching logs, quick pulse surveys,

learning walks, teacher educator observations, or shared trackers, yet powerful enough to show whether coaching is timely, consistent, and effective. When tracked with discipline, they ensure candidates are not left to the chance of who coaches them, but are instead supported by a system intentionally designed for their growth.

From Coaching by Chance to Coaching by Design

The challenge is clear. Too often, candidates learn by chance rather than by design. But the

solution is within reach. Every program has the people and the commitment to make coaching the throughline of preparation. What is missing is the choice to adopt one shared system, one effective coaching cycle, one common language, and one set of expectations that make feedback consistent, timely, and actionable across coursework and clinical experiences.

This is not about adding more requirements. It is about redirecting existing effort toward what matters most: coaching that models, rehearses, and reinforces the instructional skills candidates must be proficient in to teach well from day one.

Programs can start by agreeing on a shared coaching cycle, training every teacher educator to use it, and tracking a few simple measures to ensure quality. Together, these steps turn feedback from scattered advice into a reliable system for candidate growth. Every candidate deserves more than the luck of who coaches them. They deserve deliberate preparation that equips them to enter classrooms with clarity, confidence, and skill. The field can solve this challenge - and must.

Let’s make teacher preparation better together.

Calvin J. Stocker

Founder & CEO, EdPrep Partners

Stay Connected

If you're interested in learning more, exploring collaboration or technical assistance, or just want to catch up, we’d love to connect:

About EdPrep Partners

Elevating Teacher Preparation. Accelerating Change.

EdPrep Partners is a national technical assistance center and non-profit. EdPrep Partners delivers a coordinated, high-impact, hands-on technical assistance model that connects diagnostics with the support to make the changes. Our approach moves beyond surface-level recommendations, embedding research-backed, scalable, and sustainable practices that most dramatically improve the quality of educator preparation—while equipping educator preparation programs, districts, state agencies, and funders with the tools and insights needed to drive systemic, lasting change.