Beyond Access Part 4: What Strong HQIM Integration Looks Like for Candidates

A Five-Part Series on HQIM Readiness in Teacher Preparation

Inside the Program: The Teacher Educator’s Role

In methods, she was told to design lessons from scratch, filling in empty templates with objectives and activities. In her placement, her mentor encouraged her to “find your own style” and improvise when lessons went off course. When her clinical supervisor observed, the debrief focused almost entirely on classroom management, pacing, and “paying attention” to certain students. Each teacher educator offered a different message, but none grounded their guidance in the instructional materials she would later be expected to use every day. She never saw a lesson unpacked from a curriculum, never rehearsed with high-quality instructional materials, never had anyone model how to adapt a lesson while preserving its intent. More than once, she heard the materials dismissed as “scripted curriculum,” which signaled that they were second-rate, something to avoid. Surely the teacher educators around her knew best.

Instead of clarity, she carried away mixed signals and lingering doubts. If no one in my program thinks these materials are important, do I really need them at all?

Why Teacher Educator Practice Matters

When candidates receive mixed messages across courses, fieldwork, and clinical supervision, they learn to improvise rather than to plan, internalize, adapt, and facilitate with high quality instructional materials. Strong preparation depends on the daily practice of teacher educators who model, rehearse, and coach the work we expect candidates to do. Quality rises or falls with the people who prepare teachers.

Without aligned practice, programs struggle to build readiness. Expectations and language vary across courses and clinical sites, leaving candidates with generic tips rather than clear, evidence based feedback that builds toward shared criteria. Faculty and supervisors themselves are rarely coached on their own practice, which means rehearsal structures and feedback routines are uneven and uncalibrated. Many programs emphasize candidate observation and evaluation but do not apply the same focus to teacher educator effectiveness, limiting growth for both candidates and those responsible for preparing them.

By contrast, strong programs treat teacher educator practice as instructional work in its own right, work that must be modeled, coached, and calibrated with the same clarity expected of candidates. They define explicit expectations for teacher educator practice, onboard faculty and clinical supervisors to those expectations, and use shared tools for observation, coaching, and feedback. They build practice based professional learning for teacher educators that includes rehearsal of modeling moves and feedback conversations, rather than one time training. They create common language and routines across roles so candidates experience alignment rather than confusion. And they use data not only to monitor candidate performance but also to track teacher educator practice, then adjust supports accordingly. Organizations such as TeachingWorks at the University of Michigan have been focused on these teacher educator practices for over a decade.

This work is especially important for HQIM. Access to curriculum is not enough. Candidates build readiness only when teacher educators model how to select high-quality instructional materials, internalize a lesson, anticipate misconceptions, rehearse delivery, and adapt without losing alignment, and then coach those moves to shared criteria. Developmental structures must intentionally move candidates from analysis, to rehearsal, to enactment, using the same HQIM or HQIM that coheres to the same criteria, that they will teach on day one. Coursework and clinical experience alignment becomes a condition for growth. When all teacher educators reinforce the same expectations for HQIM, candidate development accelerates.

Ultimately, programs must hold teacher educators accountable for the same practices they expect of candidates: modeling and labeling HQIM use in their own teaching, designing rehearsals that cover the developmental trajectory of the candidate, coaching to evidence of candidate practice of pedagogies and/or student learning using program wide criteria, and calibrating expectations through co-observation and video. These expectations reflect the EdPrep Performance Framework focus on practice based experiences, high impact teacher educator practices, and formal coaching and feedback structures.

Investing in teacher educators raises the ceiling for both candidates and the P-12 students they will teach. Programs that define, develop, and coach teacher educator practice see clearer expectations, stronger feedback, and candidates who are more ready to teach with high quality instructional materials.

Core Competencies and Approaches for HQIM Ready Teacher Educators

Strong preparation requires strong preparation practices, and quality teaching at every level. If we expect teacher candidates to select, internalize, adapt, and facilitate high quality instructional materials, then the faculty and clinical supervisors responsible for their development must model, label, and provide opportunities to rehearse those same practices and hold themselves accountable to them. Too often, preparation programs begin and end with giving candidates access to curriculum. But access alone is insufficient. It is the practices of teacher educators, how they model and label HQIM use, the developmental experiences they design to move candidates from analysis, to representations and approximations, to enactment, and the coaching and feedback they provide aligned to program wide criteria that shape candidate readiness.

Being HQIM ready as a teacher educator means more than being aware of a curriculum, or providing candidates with access to it. It means planning coursework and field experiences around high quality materials, modeling instructional decision making in real time, and supporting candidates in applying these materials with integrity and purpose. It means understanding not just the content of HQIM, but the instructional shifts they require. Programs must ensure all teacher educators, course instructors, clinical supervisors, and support staff are aligned around a shared vision of HQIM use and candidate expectations. That vision must be implemented consistently, reinforced with clear structures and routines, and supported with the same intentional development we expect for candidates.

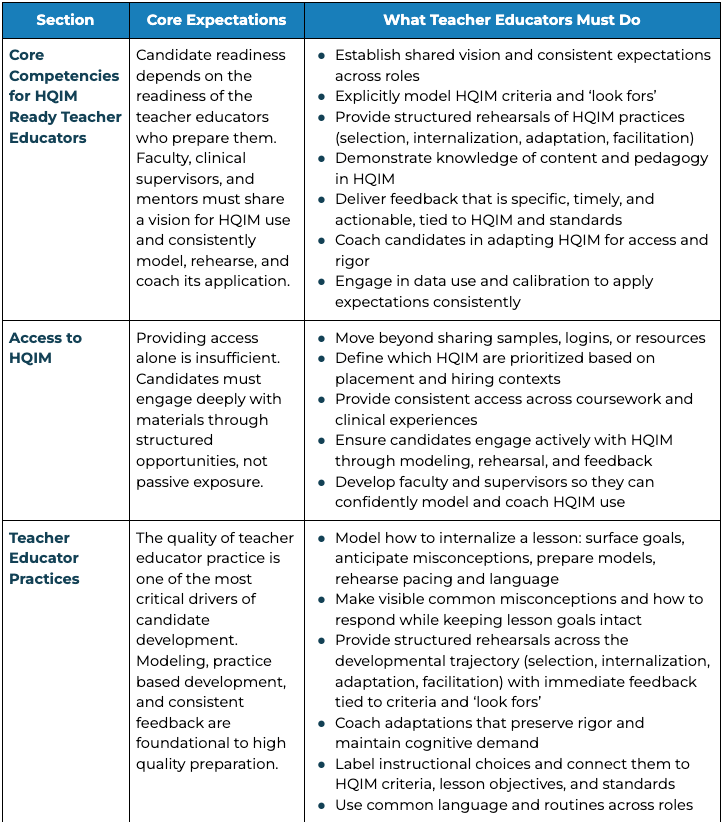

Core Competencies for HQIM Ready Teacher Educators

The readiness of candidates with high quality instructional materials depends first on the readiness of the teacher educators who prepare them: faculty, clinical supervisors, and mentors must share a vision for HQIM use and consistently model, rehearse, and coach its application. The core competencies below outline the practices that determine whether candidates graduate HQIM ready.

Shared Vision and Language

Establish clear and consistent expectations for HQIM use and for teacher educator practices across faculty, clinical supervisors, and mentors. Ensure that every candidate experiences the same language, criteria, and developmental progression.

Modeling and Labeling

Explicitly model HQIM criteria and ‘look fors’ through model lessons. Label the instructional moves, decisions, and success criteria so candidates see both the what and the why.

Rehearsals

Provide structured opportunities for candidates to rehearse HQIM practices, including selection, internalization, adaptation, and facilitation. Rehearsals should take place in safe settings with immediate feedback and coaching, anchored in shared criteria and look fors.

Knowledge of Content and Pedagogy in HQIM

Demonstrate deep understanding of both the content and the pedagogical approaches embedded in HQIM. Highlight lesson priorities, make connections to standards, anticipate common misconceptions, and surface the instructional routines and representations that help students reach grade level expectations.

Feedback That Moves Learning

Deliver specific, timely, accurate, and actionable feedback tied to lesson goals, standards, and HQIM use. Feedback should occur in both coursework and clinical experiences, using shared criteria and ‘look fors’ across faculty, supervisors, and mentors to ensure consistency.

Adaptation Coaching for Access and Rigor

Guide candidates in making integrity preserving adjustments that expand access for multilingual learners, students with disabilities, and students with unfinished learning, while maintaining the rigor and intent of HQIM.

Data Use and Calibration

Engage in regular calibration using shared tools and observation routines so that all teacher educators apply expectations consistently. Use data on candidate performance and teacher educator practices to refine coaching and support.

HQIM readiness cannot be achieved by candidates alone. Candidate preparation depends on teacher educators who consistently model, rehearse, and provide feedback using the same language and expectations, and who take responsibility for preparing them. When programs invest in HQIM ready teacher educators, they are ultimately investing in HQIM ready candidates.

1. Access to HQIM

In many preparation programs, providing candidates with access to high quality instructional materials is treated as a solution. A curriculum sample is shared. A resource room is stocked. A login is issued. And while access is necessary, it is far from sufficient.

Access without intentional development results in passive exposure, not instructional readiness. Candidates may:

- Skim a lesson without fully internalizing it

- Pull excerpts for an assignment without seeing the larger structure

- Develop their own materials disconnected from the realities of P-12 classrooms

Without structured opportunities to engage with HQIM, alongside explicit modeling, labeling, rehearsal, and feedback, candidates rarely develop the habits or fluency required for implementation with integrity.

Programs and the teacher educators within must move beyond access. They should:

- Define which HQIM are prioritized based on placement and hiring contexts

- Provide consistent access across coursework and clinical experiences

- Ensure candidates are supported by all teacher educators to engage deeply, not just interact superficially

- Develop faculty and supervisors so they can model and label HQIM use

If teacher educators themselves are unfamiliar with HQIM, or not equipped to model and coach its use, candidates will graduate underprepared for the systems they are entering.

2. Teacher Educator Practices

The quality of teacher educator practice is one of the most critical drivers of candidate development. EdPrep Partners’ EdPrep Performance Framework emphasizes that modeling, practice-based development, and aligned and consistent (quality) feedback are foundational to quality preparation. In HQIM aligned preparation, teacher educators must go beyond assigning curriculum tasks.

To prepare candidates for HQIM readiness, teacher educators should:

- Model how to internalize a lesson

Demonstrate to candidates how to study a lesson with clarity and intentionality. This includes surfacing the standard and goal, working through student tasks, anticipating misconceptions, preparing models and questions, and rehearsing pacing and language.

- Anticipate misconceptions

Make visible the common misunderstandings and sticking points that candidates should expect when teaching (with the HQIMs, as well), and show how instructional moves can respond to them while keeping the lesson goal intact.

- Rehearse delivery with candidates

Provide structured opportunities to practice HQIM aligned routines in low stakes settings. These rehearsals should move across the developmental trajectory: evaluating and selecting materials, internalizing lessons, adapting tasks for rigor and access, and facilitating delivery. Immediate feedback aligned to the criteria & ‘look fors’, along with coaching tied to these shared criteria, ensures candidates improve with each cycle.

- Adapt without losing alignment

Coach candidates in making precise adjustments for multilingual learners, students with disabilities, or students with unfinished learning. Emphasize adaptations that preserve rigor, maintain cognitive demand, and connect back to the core instructional goals of the lesson.

- Label instructional choices and connect them to standards and criteria

Name the decisions made while modeling or coaching, and tie them back to the shared HQIM criteria, ‘look fors’, lesson objectives, and/or state standards. This helps candidates see not only what was done, but why it matters for student learning.

HQIM use cannot be treated as a checklist. It must be embedded throughout candidate development. When course instructors, clinical supervisors, and mentors use common language, model the same developmental trajectory, and provide feedback aligned to shared criteria & ‘look fors’, candidates experience true preparation. As well, alignment across coursework and clinical experiences is a condition for growth in candidate readiness.

To support HQIM aligned development, teacher educators should:

- Use common language and routines across roles so that faculty, supervisors, and mentors send coherent messages instead of conflicting ones.

- Model and label each stage of HQIM use: Selection, internalization, adaptation, and facilitation - making visible the choices and criteria that guide strong implementation.

- Provide structured rehearsal opportunities where candidates practice HQIM routines in low stakes settings, receive immediate coaching, and refine their performance before working with P-12 students.

- Offer actionable and specific feedback on candidate planning, delivery, and decision making, always tied to evidence of student learning and program wide criteria.

- Connect all feedback to standards and lesson goals, rather than giving general advice or impressions of “good teaching.”

- Reinforce HQIM expectations across every touchpoint: Coursework, field-based experiences/candidate observation, clinical supervision, coaching, signature assignments, etc. - so candidates experience consistency and consistent reinforcement of what is expected.

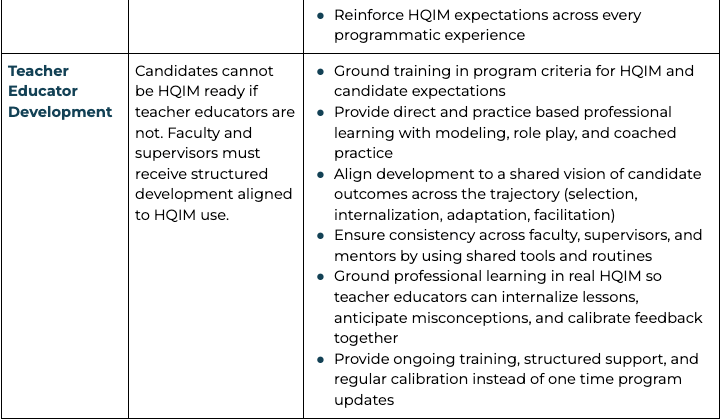

3. Teacher Educator Development

Programs cannot expect candidates to be HQIM ready if the faculty and supervisors preparing them are not. Being a content expert or an experienced teacher is not enough. Teacher educators must receive structured development to model, label, coach, and provide feedback aligned to HQIM use.

High quality teacher educator development should be:

- Grounded in program criteria for HQIM and candidate expectations

Development should begin with the program’s own definition of HQIM and clear descriptions of what candidates must know and be able to do by specific performance gateways and by program completion. - Direct and practice-based

Teacher educators need opportunities to rehearse the same instructional moves and coaching strategies they are expected to use with candidates. Professional learning should include modeling, role play, and coached practice. - Aligned to a shared vision of candidate outcomes

All teacher educators should reinforce the same developmental trajectory - evaluation and selection, internalization, adaptation, and facilitation - so candidates experience alignment across courses and clinical settings. - Consistent across roles

Faculty, clinical supervisors, and mentors must use common expectations, shared routines, and the same observation and feedback tools to avoid cognitive burdens on candidates. - Grounded in real HQIM

Training must use the actual curricula that candidates are working with in coursework and field placements, giving teacher educators the chance to internalize lessons, anticipate misconceptions, and calibrate their approaches and feedback together.

Too often, professional learning for teacher educators centers on program updates while leaving untouched the major instructional priorities of P-12 districts, such as HQIM. Ongoing training, structured support, and regular calibration are essential. Quality preparation requires quality preparation practices, and those practices must be developed with the same intentionality expected for candidates.

Putting it All Together

Strong preparation requires strong preparation practices, and quality teaching at every level. If candidates are expected to select, internalize, adapt, and facilitate high quality instructional materials, then teacher educators must be able to model, label, rehearse, and coach those same practices with consistency. Being HQIM ready as a teacher educator means more than awareness of curriculum or providing access to it. It requires planning coursework and field experiences around HQIM, modeling instructional decision making in real time, and supporting candidates in applying materials with integrity and purpose.

Included in the appendix is the What Strong HQIM Integration Looks Like for Teacher Educators, which defines the core competencies and approaches for HQIM ready teacher educators. Programs can use this table as a roadmap to align faculty, clinical supervisors, and mentors around the shared practices, structures, and development to ensure HQIM ready candidates.

Up Next: Strong HQIM Integration for Programs

Part 5 in the Beyond Access series will explore how programs can design HQIM-focused preparation from start to finish. We will look at how programs can best prepare for the HQIM landscape of their district partners, define a shared vision for what HQIM readiness looks like for both candidates and teacher educators, and intentionally map developmental experiences across coursework and clinical so candidates build readiness over time.

Let’s make teacher preparation better together.

Up Next: Strong HQIM Integration for Teacher Educators

Candidates should not have to outpace the people who are responsible for developing them. Faculty, clinical supervisors, and mentors shape how candidates experience HQIM through the developmental opportunities they provide, skills they model, the feedback they provide, and the expectations they reinforce. In the next part of our Beyond Access series, we will explore what strong HQIM integration looks like for teacher educators - the daily preparation practices that will make “curriculum readiness” a reality for every candidate.

Let’s make teacher preparation better together.

Appendix

What Strong HQIM Integration Looks Like for Teacher Educators

Stay Connected

If you're interested in learning more, exploring collaboration or technical assistance, or just want to catch up, we’d love to connect:

About EdPrep Partners

Elevating Teacher Preparation. Accelerating Change.

EdPrep Partners is a national technical assistance center and non-profit. EdPrep Partners delivers a coordinated, high-impact, hands-on technical assistance model that connects diagnostics with the support to make the changes. Our approach moves beyond surface-level recommendations, embedding research-backed, scalable, and sustainable practices that most dramatically improve the quality of educator preparation—while equipping educator preparation programs, districts, state agencies, and funders with the tools and insights needed to drive systemic, lasting change.