Beyond Access Part 2: Aligning with the Quality Curriculum that Matters Most

A Five-Part Series on HQIM Readiness in Teacher Preparation

The Curriculum Box

In Part 1 of this series, we met a first year teacher standing in her classroom on day one, facing a choice: rely on the training she received to design lessons from scratch, or use the high quality instructional materials her district provided - materials she had never practiced with.

Now picture her again. In the corner of the room sits a sealed curriculum box from the district. The district has spent thousands of dollars on this curriculum, a resource that in many schools is a prized possession. Inside are teacher guides, student workbooks, and assessments - the very materials her district expects her to use to deliver instruction and that are meant to improve P-12 student outcomes. She pulls off the cellophane, opens the flaps, and begins taking out the resources one by one. This is the moment she realizes that while she now has all of these materials, she does not know how to use them. Her preparation program may have mentioned curriculum materials, even had a resource room filled with sample curricula, but she never really engaged with them in her coursework, and she never had the chance to practice teaching with them during student teaching.

What happens when teacher preparation leaves candidates “opening the box” for the first time only when they enter their own classroom as the teacher of record?

District Investments Depend on Preparation

Teacher preparation cannot truly align coursework, clinical practice, or teacher educator development without a clear view of what curriculum materials districts expect new teachers to use. In reality, the majority of a program’s completers are typically hired into just a handful of local or regional districts for most programs, and in core subjects like reading and math many of those districts often use the same high quality instructional materials. Knowing the local curriculum landscape means a preparation program can make intentional choices about how faculty model teaching with it, what candidates rehearse their instruction with, and how clinical supervisors and faculty members alike coach and provide feedback on. For example, Louisiana now requires P-12 districts to publish the curricula they are using, which helps nearby teacher preparation programs identify which materials are most relevant for their candidates given where they are likely to student teach or be hired.

Districts invest millions of dollars in curriculum adoption because research shows that strong instructional materials, in the hands of well prepared teachers, can significantly accelerate P-12 student learning. Choosing a top tier curriculum can be as powerful a lever for improving P-12 student achievement as the difference between a novice and an experienced teacher. But those investments only pay off if novice teachers enter classrooms ready to use the materials with skill and confidence. If new teachers are not prepared to use a rigorous, standards aligned curriculum, they often end up defaulting to piecemeal lessons from Pinterest or other unvetted sources. The Education Policy Initiative at Carolina (EPIC) found that more than 90 percent of novice teachers turned to Teachers Pay Teachers and about 70 percent used Pinterest when district materials were not provided.. This gap in training has serious implications for students: when new teachers are not equipped to use strong materials, their students miss out on grade level content, and because students furthest from opportunity are more likely to have novice teachers, inequities in access to quality instruction are exacerbated.

Districts purchase HQIM expecting them to drive learning gains, but that can only happen if teachers know how to use them.

If preparation programs do not begin with clarity about the curricula their candidates will use when teaching, how can those candidates be expected to meet expectations and lead improved P-12 outcomes when they arrive on day one?

When Preparation Falls Short

Too often, preparation programs do not ask their partner districts what curriculum materials they use. Instead, candidates are taught to design lessons from scratch or are given access to a resource room filled with materials, but without meaningful opportunities to engage with them. Faculty and supervisors may acknowledge curriculum in theory, yet do not model or coach with the very materials districts expect new teachers to use.

The result is that many candidates graduate confident in writing lesson plans but unready to adapt and deliver instruction from the curriculum they will be required to implement as teachers of record. Research has shown that teacher preparation programs frequently train candidates to plan lessons in isolation, selecting standards, activities, and assessments on their own, even as P-12 districts increasingly require teachers to use high quality instructional materials. The more relevant skill for novice teachers is not designing lessons from scratch but learning to internalize, adapt, and deliver rigorous, standards aligned lessons from adopted curricula.

When preparation fails to provide guided practice in doing so, the opportunity to connect preparation with practice is missed, not because it is impossible, but because curriculum alignment has not been treated as foundational.

If a preparation program never takes the first step of asking districts about the materials they have adopted, how can it claim to be preparing candidates for the classrooms they will actually enter?

What States and Programs Are Showing the Field

Some educator preparation programs explain that it would be impossible to prepare candidates for every possible curriculum across all their P-12 partner districts. But the reality is different. As described in the first part of this series, the criteria for what makes instructional materials high quality are consistent across states and national partners. HQIM must be standards aligned, systematically sequenced, include embedded assessments, and provide the support(s) teachers need to deliver instruction with rigor and clarity (see Part 1: The Case for HQIM in Teacher Preparation for the full definition). Most curricula that meet these criteria share common structures and similar demands on teachers and P-12 students.

In practice, the number of high quality curricula that districts adopt at scale is relatively small. For example, in Louisiana the state’s review process has identified just over 50 curricula that meet Tier 1 criteria across subjects, and more than 80 percent of school systems in the state have adopted these Tier 1 programs as their curriculum of choice. As a result, over 90 percent of Louisiana students now have access to a high quality curriculum in core subjects.

Tennessee has pursued a similar approach. State leaders recognized that educator preparation is a critical driver of HQIM implementation and launched the HQIM Network to help teacher preparation programs integrate widely adopted literacy curricula into their coursework and clinical experiences. In one network, after candidates completed modules aligned to a common ELA curriculum, their ability to identify standards aligned materials and make rigorous instructional decisions increased significantly. Assessment scores rose by 25 percentage points, and the share of candidates selecting approaches that supported rigorous instruction increased from 45 percent to 77 percent.

After asking districts about their curriculum choices, programs can uncover a clear and manageable picture of what matters most. Instead of dozens of disparate resources, programs often find that a small set of curricula account for the vast majority of classroom use in their partner districts. This makes alignment possible and practical.

The evidence points to a consistent conclusion: preparation is not about training candidates on dozens of different materials. It is about aligning preparation to the relatively small number of high quality instructional materials and the common elements that define their quality that candidates are most likely to encounter in the classrooms where they will teach.

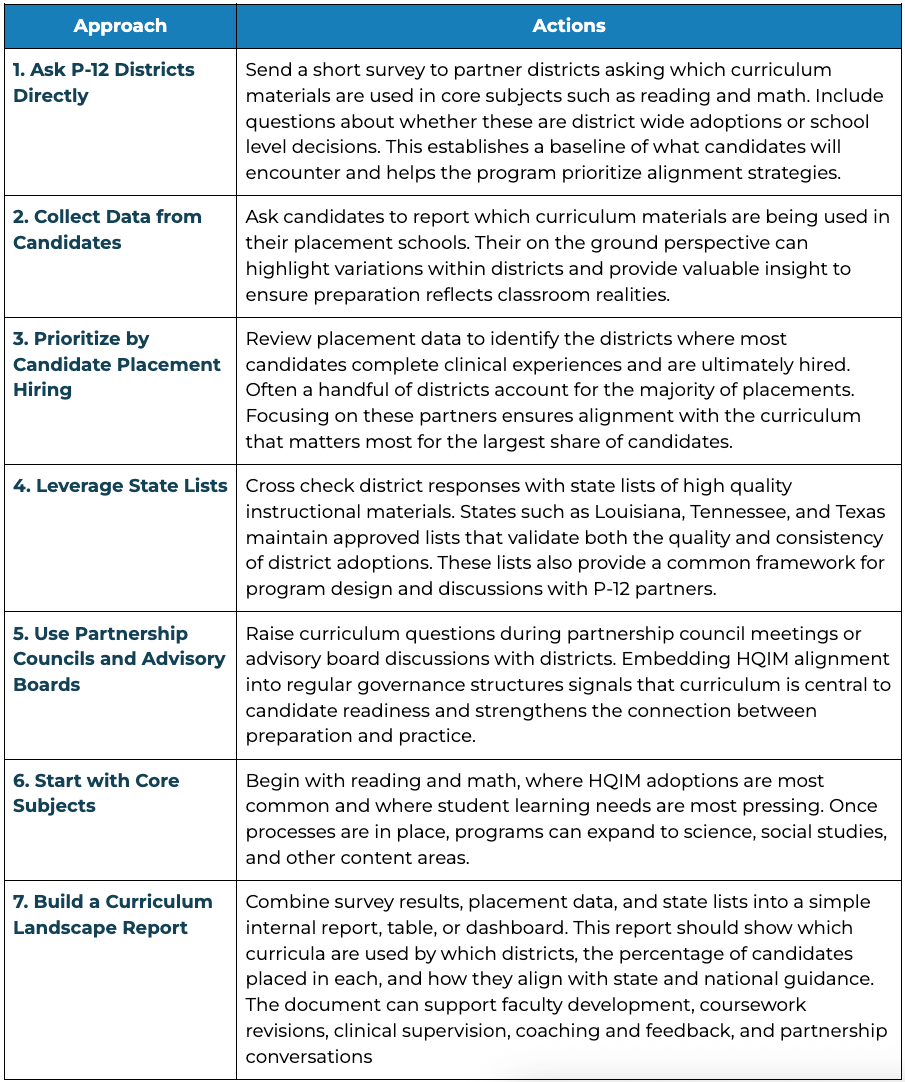

Steps Programs Can Take Now

Preparation programs can take practical steps to ensure candidates are not opening the curriculum box for the first time when they enter the classroom as teacher of record. Below are seven approaches programs can use to build clarity and alignment.

Up Next: Strong HQIM Integration for Candidates

Knowing is not enough. Readiness for candidates comes from practice. In the next part of our Beyond Access series, we will explore what it takes for teacher candidates to move beyond exposure to high quality instructional materials and into authentic preparation and use. How can preparation programs ensure that candidates leave ready not only to recognize HQIM, but to use it with skill, purpose, and impact from day one?

Let's make teacher preparation better together.

Stay Connected

If you're interested in learning more, exploring collaboration or technical assistance, or just want to catch up, we’d love to connect:

About EdPrep Partners

Elevating Teacher Preparation. Accelerating Change.

EdPrep Partners is a national technical assistance center and non-profit. EdPrep Partners delivers a coordinated, high-impact, hands-on technical assistance model that connects diagnostics with the support to make the changes. Our approach moves beyond surface-level recommendations, embedding research-backed, scalable, and sustainable practices that most dramatically improve the quality of educator preparation—while equipping educator preparation programs, districts, state agencies, and funders with the tools and insights needed to drive systemic, lasting change.